There

are a number of ideas relevant to the preparation of this proposal which must

be noted down:

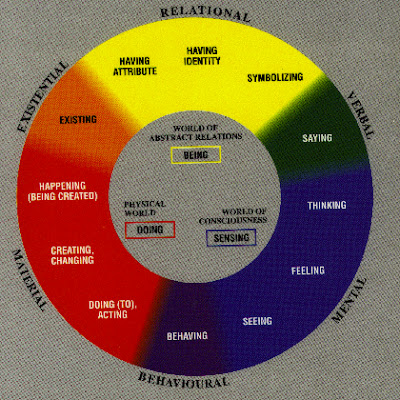

Norman

Fairclough presents a diagrammatic representation of what he describes as

social conditions of production as related to language:

Fairclough

says the “text represents two types of content: “social reality”, and “social

relations and social identities”. Social reality corresponds to what Michael

Halliday calls “ideational meaning”. “Social relations and social identities”

are what Halliday calls “interpersonal meaning”, although in his account of

interpersonal meaning Halliday focuses mainly on “social relations”. Fairclough

does not deal with what Halliday calls the “textual function of language.

The

middle layer of Fairclough’s diagram represents the writing and the reading of

texts. He is, according to Roz Ivanic, referring to the mental, social and

physical processes, practices and procedures involved in creating the text.

People are located in this layer, thinking and doing things in the process of

producing and interpreting texts. This layer of the diagram includes the role

of social interaction in discourse.[…] Related specifically to the production

process of writing, this layer connects the wider social context to the words on

the page through the head of the writer. It represents the writer’s mental

struggles which lead, among other things, to particular identities being

written into the text. […]The outer layer [is], the social context which shapes

discourse production, discourse interpretation and the characteristics of the

text itself. This is the “context of culture”.

|

| Halliday |

Mikhail

Bakhtin summarizes:

…language has been completely taken over, shot through

with intentions and accents. For any individual consciousness living in it,

language is not an abstract system of normative forms but rather a concrete heteroglot (see below)

conception of the world. All words have a “taste” of a profession, a genre, a

tendency, a party, a particular work, a particular person, a generation, an age

group, the day and hour. Each word tastes of the context and contexts in which

it has lived its socially charged life; all words and forms are populated by

intentions….Language is not a neutral medium that passes freely and easily into

the private property of the speaker’s intentions; it is populated, overpopulated

– with the intentions of others.

Heteroglossia

In linguistics, the term heteroglossia describes

the coexistence of distinct varieties within a single linguistic code. The term

translates the Russian разноречие [raznorechie]

(literally "different-speech-ness"), which was introduced by the

Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin in his 1934 paper

Слово в романе [Slovo v romane], published in English as "Discourse in the

Novel."

Bakhtin argues that the

power of the novel originates in the coexistence of, and conflict between, different

types of speech: the speech of characters, the speech of narrators, and even

the speech of the author. He defines heteroglossia as "another's speech in

another's language, serving to express authorial intentions but in a refracted

way." It is important to note that Bakhtin identifies the direct narrative

of the author, rather than dialogue between characters, as the primary location

of this conflict.

Languages as points of view

Bakhtin viewed the modernist

novel as

a literary form best suited for the exploitation of heteroglossia, in direct

contrast to epic poetry (and, in a lesser degree, poetry

in general). The linguistic energy of the novel was seen in its expression of

the conflict between voices through their adscription to different elements in

the novel's discourse.

Any language, in Bakhtin's

view, stratifies into many voices: "social dialects, characteristic group behaviour,

professional jargons, generic languages, languages of generations and age

groups, tendentious languages, languages of the authorities, of various circles

and of passing fashions." This diversity of voice is, Bakhtin asserts, the

defining characteristic of the novel as a genre.

Traditional stylistics, like

epic poetry, do not share the trait of heteroglossia. In Bakhtin's words,

"poetry depersonalizes "days" in language, while prose, as we

shall see, often deliberately intensifies difference between them..."

Extending his argument,

Bakhtin proposes that all languages represent a distinct point of view on the

world, characterized by its own meaning and values. In this view, language is

"shot through with intentions and accents," and thus there are no

neutral words. Even the most unremarkable statement possesses a taste, whether

of a profession, a party, a generation, a place or a time. To Bakhtin, words do

not exist until they are spoken, and that moment they are printed with the

signature of the speaker.

Bakhtin identifies the act

of speech, or of writing, as a literary-verbal performance, one that requires

speakers or authors to take a position, even if only by choosing the dialect in

which they will speak. Separate languages are often identified with separate

circumstances. Bakhtin gives the example of an illiterate peasant, who speaks

Church Slavonic to God, speaks to his family in their own peculiar dialect,

sings songs in yet a third, and attempts to emulate officious high-class

dialect when he dictates petitions to the local government. The prose writer,

Bakhtin argues, must welcome and incorporate these many languages into his

work.

The hybrid utterance

The hybrid

utterance, as defined by Bakhtin, is a passage that employs only a single speaker

-- the author, for example -- but one or more kinds of speech. The

juxtaposition of the two different speeches brings with it a contradiction and

conflict in belief systems.

In examination

of the English comic novel, particularly the works of Dickens, Bakhtin

identifies examples of his argument. Dickens parodies both the 'common tongue'

and the language of Parliament or high-class banquets, using concealed

languages to create humour. In one passage, Dickens shifts from his authorial

narrative voice into a formalized, almost epic tone while describing the work

of an unremarkable bureaucrat; his intent is to parody the self-importance and

vainglory of the bureaucrat's position. The use of concealed speech, without

formal markers of a speaker change, is what allows the parody to work. It is,

in Bakhtin's parlance, a hybrid utterance. In this instance the conflict is

between the factual narrative and the biting hyperbole of the new,

epic/formalistic tone.

Bakhtin goes on

to discuss the interconnectedness of conversation. Even a simple dialogue, in

his view, is full of quotations and references, often to a general

"everyone says" or "I heard that.." Opinion and information

is transmitted by way of reference to an indefinite, general source. By way of

these references, humans selectively assimilate the discourse of others and

make it their own.

Bakhtin

identifies a specific type of discourse, the "authoritative

discourse," which demands to be assimilated by the reader or listener;

examples might be religious dogma, or scientific theory, or a popular book.

This type of discourse as viewed as past, finished, hierarchically superior,

and therefore it demands "unconditional allegiance" rather than

accepting interpretation. Because of this, Bakhtin states that authoritative

discourse plays an insignificant role in the novel. Because it is not open to

interpretation, it cannot enter into hybrid utterance.

Bakhtin

concludes by arguing that the role of the novel is to draw the authoritative

into question, and to allow that which was once considered certain to be become

conflicted and open to interpretation. In effect, novels not only function

through heteroglossia, but must promote it; to do otherwise is an artistic

failure.

Influence of the concept

Bakhtin's view of heteroglossia

has been often employed in the context of the postmodern critique of the perceived

teleological and authoritarian character of modernist art and culture. In

particular, the latter's strong disdain for popular forms of art and literature

— archetypically expressed in Adorno and Horkheimer's analysis of the culture industry — has been criticised as

a proponent of monoglossia ; practitioners of cultural studies have used Bakhtin's

conceptual framework to theorise the critical reappropriation of mass-produced

entertainment forms by the public.

Dorothy Hale applied the

concept of heteroglossia to African-American literature in "Bakhtin in

African American Literary Theory," pointing to a slave narrator

remembering his bondage or the racial narrative of the blues as distinctly

African-American voices that come into conflict with other dialects. In Hale's

view, heteroglossia is similar to W. E. B. Dubois' view of the African American

double consciousness, torn between the American experience and African

heritage. African American literature, by nature, contains a powerful and

persistent heteroglossia. To Hale this is not simply a literary technique but a

sign of African-American linguistic identity.

Hale criticizes DuBois for

limiting double consciousness to African-Americans alone, identifying

African-American double consciousness as a special case of universal

heteroglossia, and comparing the plight of the African-American to Bakhtin's

hypothetical peasant. To Hale, the fact that heteroglossia is a social

construction offers hope for equality to African-Americans because it implies

that they are different and unequal only because society makes them so, rather

than because of any inherent trait.

No comments:

Post a Comment